4차 산업혁명은 여전히 기술적인 혁명의 또 다른 레이블일 지도 모른다.

다만, 그 기술의 향유 주체가 더 이상 인간(만)이 아닐 수 있다는 게

그 이전 모든 차수와 구별된다.

살아남은 인간들에겐, 그래서 결국 많은 자문을 남기는

보통의 ‘혁명’이 또한 될 것이다.

2017-12-26

2017-08-27

2017-08-26

2017-08-20

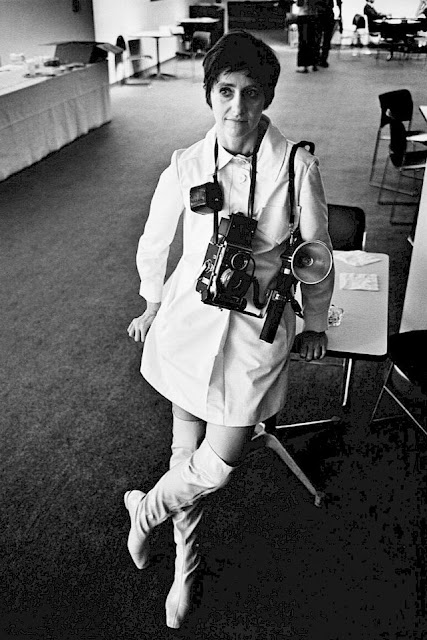

Philip-Lorca diCorcia (U.S., 1951-)

Introduction from Wikipedia

Biography

DiCorcia was born in 1951 in Hartford, Connecticut. His family is of Italian descent, having moved to the United States from Abruzzo. He attended the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, where he earned a Diploma in 1975 and a 5th year certificate in 1976.Work

DiCorcia alternates between informal snapshots and iconic quality staged compositions that often have a baroque theatricality.[3]

Using a carefully planned staging, he takes everyday occurrences beyond the realm of banality, trying to inspire in his picture's spectators an awareness of the psychology and emotion contained in real-life situations.[4] His work could be described as documentary photography mixed with the fictional world of cinema and advertising, which creates a powerful link between reality, fantasy and desire.[3]

During the late 1970s, during diCorcia's early career, he used to situate his friends and family within fictional interior tableaus, that would make the viewer think that the pictures were spontaneous shots of someone's everyday life, when they were in fact carefully staged and planned in beforehand.[4][5] His work from this period is associated with the Boston School of photography.[6] He would later start photographing random people in urban spaces all around the world. When in Berlin, Calcutta, Hollywood, New York, Rome and Tokyo, he would often hide lights in the pavement, which would illuminate a random subject in a special way, often isolating them from the other people in the street.[7]

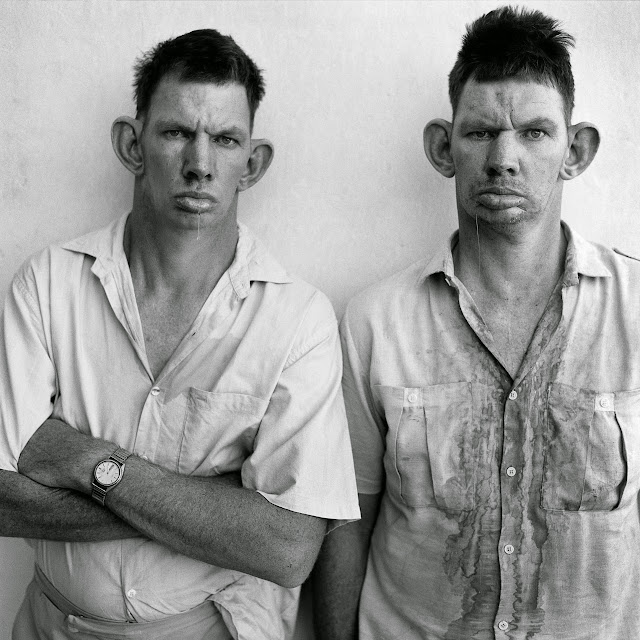

His photographs would then give a sense of heightened drama to the passers-by accidental poses, unintended movements and insignificant facial expressions.[8] Even if sometimes the subject appears to be completely detached to the world around him, diCorcia has often used the city of the subject's name as the title of the photo, placing the passers-by back into the city's anonymity.[8] Each of his series, Hustlers, Streetwork, Heads, A Storybook Life, and Lucky Thirteen, can be considered progressive explorations of diCorcia’s formal and conceptual fields of interest. Besides his family, associates and random people he has also photographed personas already theatrically enlarged by their life choices, such as the pole dancers in his latest series.

His pictures have black humor within them, and have been described as "Rorschach-like", since they can have a different interpretation depending on the viewer.[9] As they are planned beforehand, diCorcia often plants in his concepts issues like the marketing of reality, the commodification of identity, art, and morality.[10]

In 1989, financed by a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship of $45,000, DiCorcia began his “Hustlers” project. Starting in the early 1990s, he made five trips to Los Angeles to photograph male prostitutes in Hollywood. He used a 6-by-9 Linhof view camera, which he positioned in advance with Polaroid tests. At first, he photographed his subjects only in motel rooms. Later, he moved onto the streets. When the Museum of Modern Art exhibited 25 of the photographs in 1993 under the title “Strangers,” each was labeled with the name of the man who posed, his hometown, his age, and the amount of money that changed hands.[11]

In 1999, DiCorcia set up his camera on a tripod in Times Square, attached strobe lights to scaffolding across the street and took a random series of pictures of strangers passing under his lights.[12]

Originally published in W as a result of a collaboration with Dennis Freedman between 1997 and 2008, DiCorcia produced a series of fashion stories in places like Havana, Cairo and New York.[13]

Publications

- Heads. Göttingen: Steidl, 2001. ISBN 3882434414. Luc Sante and diCorcia.

- Philip-Lorca diCorcia. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2003. ISBN 0870701452. Peter Galassi and diCorcia.

- A Storybook Life. Santa Fe, NM: Twin Palms, 2003.

- Philip-Lorca diCorcia. Steidl/Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, 2007. ISBN 3865213855. Bennett Simpson (author), Jill Medvedow (foreword), Lynne Tillman (contributor), diCorcia (photographer).

Exhibitions

Solo exhibitions

- Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY.[citation needed]

- Centre National de la Photographie, Paris.[citation needed]

- Whitechapel Art Gallery, London.[citation needed]

- Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid.[citation needed]

- Art Space Ginza, Tokyo.[citation needed]

- Sprengel Museum, Hannover.[5]

- Thousand, David Zwirner Gallery, New York, March 2009. One thousand actual-size reproductions of diCorcia's Polaroids.[2]

- Roid, Sprüth Magers, London, 2011. A series of diCorcia's Polaroids.[14][15]

- The Hepworth Wakefield, England, February 2014. His first UK retrospective.

Exhibitions with others

- Pleasures and Terrors of Domestic Comfort traveling exhibition organized by Museum of Modern Art, 1991.

- 1997 Whitney Biennial, Whitney Museum of American Art

- Cruel and Tender, Tate Modern, London, 2003.

- Fashioning Fiction in Photography Since 1990, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2004.

- Carnegie Museum of Art’s 54th Carnegie International exhibition, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Collections

DiCorcia's work is held in the following public collections:

- Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

- Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris.

- Museum Folkwang, Essen.

- Museum of Modern Art, New York.

- Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

- Tate Gallery, London.

- Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

Selected awards

- 1980: Artist Fellowship, National Endowment for the Arts.

- 1986: Artist Fellowship, National Endowment for the Arts.

- 1987: John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship.

- 1989: Artist Fellowship, National Endowment for the Arts.

- 1998: Alfred Eisenstaedt Award, Life Magazine, Style Essay.

- 2001: Infinity Award for Applied Photography, International Center of Photography.

- 2013: III International Photography Award Alcobendas, Spain.

External links

In 2006, a New York trial court issued a ruling in a case involving one of his photographs. One of diCorcia's New York random subjects was Ermo Nussenzweig, an Orthodox Jew who objected on religious grounds to diCorcia's publishing in an artistic exhibition a photograph taken of him without his permission. The photo's subject argued that his privacy and religious rights had been violated by both the taking and publishing of the photograph of him. The judge dismissed the lawsuit, finding that the photograph taken of Nussenzweig on a street is art - not commerce - and therefore is protected by the First Amendment.[16]

Manhattan state Supreme Court Justice Judith J. Gische ruled that the photo of Nussenzweig—a head shot showing him sporting a scraggly white beard, a black hat and a black coat—was art, even though the photographer sold 10 prints of it at $20,000 to $30,000 each. The judge ruled that New York courts have "recognized that art can be sold, at least in limited editions, and still retain its artistic character (...) [F]irst [A]mendment protection of art is not limited to only starving artists. A profit motive in itself does not necessarily compel a conclusion that art has been used for trade purposes."[17]

The case was appealed and dismissed on procedural grounds.[18][19][20]

References

1.Profile: Philip-Lorca diCorcia by Barry Schwabsky

2.Release: David Zwirner - Philip-Lorca diCorcia: Thousand (February 27 - March 28, 2009). Retrieved on May 20-2009 (PDF).

3.Whitechapel Art Gallery, London Retrieved on November 23-2007.

4.Carnegie International - Artist Bio. Retrieved on November 23-2007.

5.http://www.lslimited.com/dicorcia/pl.html Leslie Simitch Limited - Philip-Lorca diCorcia. Retrieved on November 23-2007.

6."Emotions and Relations: Photographs by David Armstrong, Nan Goldin, Philip Lorca DiCorcis, Mark Morrisroe, and Jack Pierson". photo-eye. Taschen. Archived from the original on April 25, 2015.

7.Unfamiliar Streets. Katherine A. Bussard. The Photographs of Richard Avedon, Charles Moore, Martha Rosler, and Philip-Lorca diCorcia. Philip-Lorca diCorcia Analogues of Reality. Yale University Press. 2012. p156. Referenced April 6, 2015.

8.Philip-Lorca diCorcia: Streetwork Retrieved on November 23-2007.

9.http://artscenecal.com/ArticlesFile/Archive/Articles1997/Articles1097/PdiCorciaA.html

10.PHILIP-LORCA diCORCIA by Marlena Donohue Retrieved on November 23-2007.

11.Arthur Lubow (August 23, 2013), Real People, Contrived Settings: Philip-Lorca diCorcia’s ‘Hustlers’ Return to New York New York Times.

12.Philip Gefter (March 17, 2006), Street photography: A right or invasion? International Herald Tribune.

13.Cathy Horyn (February 11, 2011), Q & A: Philip-Lorca diCorcia New York Times.

14."Philip-Lorca diCorcia's 'Roid' At Sprüth Magers London". The Huffington Post. 11 June 2011. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

15."Philip Lorca diCorcia: Roid". London: The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

16.NY Courts.gov - Nussenzweig v DiCorcia (February 8, 2006). Retrieved on May 3, 2008.

17.American Journalism Review - Giving Offense. Retrieved on May 3, 2008.

18.Clancco - Update on Nussenzweig v. diCorcia Case (July '07). Retrieved on May 3, 2008.

19.The New York Times - Case Over ‘Heads’ Photo Is Dismissed. Retrieved on May 3, 2008.

20.Law.com - 'Art' Photo Is Not Subject to Privacy Law, Judge Finds. Retrieved on May 3, 2008.

Unfamiliar Streets. Katherine A. Bussard. The Photographs of Richard Avedon, Charles Moore, Martha Rosler, and Philip-Lorca diCorcia. Philip-Lorca diCorcia Analogues of Reality. Yale University Press. 2012. p. 156. Referenced April 6, 2015.

*from: Wikipedia; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philip-Lorca_diCorcia

Introduction from MoMA

Philip-Lorca diCorcia’s photographs straddle truth and fiction by combining real people and places—but not necessarily people and places that naturally go together. The theatricality of his images is carefully constructed: he arranges the objects of each scene and devises precise lighting and framing for every project. His work is often described as cinematic, a description that diCorcia deplores. He insists that his pictures suggest rather than elucidate a full narrative. His brand of storytelling results in unstable, unfixed images that point in certain directions but never provide a definitive map.

His earliest work, from the late 1970s, featured his friends and family in scenes that evoke loneliness, contemplation, ennui, or, occasionally, humor. In Mario, diCorcia's brother stares into an open refrigerator, his late-night mission to unearth a snack infused with inertia. The photograph couples an impression of complete stillness with the eerie, seemingly contradictory sense of witnessing a fleeting moment. Peter Galassi, former chief curator of MoMA’s Department of Photography, described the production of this image: “The subject was utterly ordinary but the photograph was carefully planned. The camera was on a tripod and the lighting was supplemented by an electronic flash hidden in the refrigerator and triggered at the moment of exposure. DiCorcia leveled the camera, adjusted and readjusted the lighting, made several Polaroid test shots and more than a few exposures, each aiming at the envisioned result.”1 DiCorcia’s acute attention to detail has become the hallmark of his process and has influenced a generation of photographers (including Katy Grannan, Justine Kurland, Alex Prager, and Alec Soth, among others) who work with controlled situations and semi-anonymous portrait subjects.

DiCorcia did not set out to become a photographer. While attending the University of Hartford, he studied with Jan Groover, who planted the idea that a photograph is not necessarily an artifact documenting a specific sliver of time; rather, a photograph should result from careful planning and orchestration. Early- and mid-20th-century photographers who also took this approach include Paul Outerbridge, Philippe Halsman, and Bill Brandt. During his graduate studies at Yale University diCorcia begin to classify himself as a photographer by first determining the kind of image-maker he did not want to be. Garry Winogrand, Lee Friedlander, and Tod Papageorge—who rapidly shot many exposures in order to get to a few final images—attempted to capture the real world at a particular moment in time from a specific point of view. Their mid-20th-century work presented diCorcia with a strand of street photography to push against at exactly the same time that color processes began to be used outside of advertising and news photography. DiCorcia deliberately chose to print in color since it was an underutilized format in fine-art photography.

MoMA presented diCorcia’s first solo museum exhibition in 1993, featuring his series Hustlers, which was made in Los Angeles between 1990 and 1992. He photographed male prostitutes he approached on Santa Monica Boulevard, paying them whatever they typically charged for their services to instead pose in scenarios he had prepared for the photo sessions. The titles of these photographs, such as Eddie Anderson; 21 Years Old; Houston, Texas; $20, list only the facts. Yet by inserting their bodies into prepared scenes in hotel rooms or on the street, diCorcia made portraits that operate in tandem with—but do not exactly reproduce—the fantasy roles these men were usually conscripted to play.

Having worked outside on the Hustlers series, diCorcia delved further into street photography. As he explained, “The elements which call into question the normal relationship of appearance to truth in photography are, for most artists of my generation, tools to enrich the experience of work rather than ends in themselves.”2 Taking the work of Garry Winogrand in particular as a starting point, diCorcia reinvigorated the genre in the 1990s by freezing the ebb and flow of a city sidewalk in images such as Los Angeles and New York. By arranging flashes and stationing his camera at a precise location, he suspended slices of time in images that have the quiet stillness of Old Master paintings. For his series Streetwork (1993–97) and Heads (2000–01), he took thousands of photographs, of which he selected only a handful for inclusion. Unlike other practitioners of street photography, diCorcia never wanted his images to propagate a moral truth or instigate social change.

When John Szarkowski, former director of MoMA's Department of Photography, included the artist in the second iteration of the Museum’s New Photography exhibition series, in 1986, he wrote, “Philip-Lorca diCorcia involves us in the issues of story and plot by constructing tableaus that withhold information that we expect to be given.”3 DiCorcia’s photographs succeed because of his will to show more and tell less.

Introduction by Kelly Sidley, Curatorial Assistant, Department of Photography, 2016

- Peter Galassi, “Photography Is a Foreign Language,” in Philip-Lorca diCorcia (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1995), 5.

- Philip-Lorca diCorcia, “Reflections on Streetwork,” in Streetwork (Salamanca, Spain: Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca, 1998), 11.

- John Szarkowki, “New Photography 2: Mary Frey, David T. Hanson, Philip Lorca diCorcia,” MoMA 41 (Autumn 1986): 2.

Labels:

diCorcia

2017-07-30

film: '세계' (世界, The World, 2004) by 지아 장커.Jia Zhangke.贾樟柯

"널 호강시켜 줘야 하는데...

여기 온 첫날 밤 침대에 누워서

기차 소리를 들으며 맹세했어

반드시 성공해서 널 행복하게 해주겠다고"

"꿈도 야무지다, 여긴 베이징이야."

"두고 봐. 호강시켜 줄 테니."

"호강 못해도 괜찮아."

- 世界, 2004

film: '임소요' (任逍遙, Unknown Pleasures, 2002) by 지아 장커.Jia Zhangke.贾樟柯

"공자와 노자 알지?"

"아니."

"장자는?"

"알아."

"'임소요'에 대해 잘 알아?"

"아니."

"'임소요' 가사가 장자의 어록에서 따온거야.

네가 하고 싶은대로 행동할 자유가 있다는 얘기지."

- 任逍遙, 2002

2017-07-28

2017-07-27

장 뤽 고다르 - 단편영화: '시대의 어둠 속에서' (In the Darkness of Time, 2002)

자신의 영화들 중 가장 독창적인 장면들을 정교하게 몽타주하여

복합적이면서도 아름다운 시간에 대한 탐구를 보여준다.

복합적이면서도 아름다운 시간에 대한 탐구를 보여준다.

장 뤽 고다르 - 단편영화: '사라예보를 기억하세요?' (Je Vous Salue, Sarajevo. 1993)

사라예보의 길에 누워 있는 세 명의 시민과 총을 든 세 명의 병사를 찍은 한 장의 사진을

바탕으로 유럽 문명과 보스니아 전쟁, 고문과 학살의 비극을 환기시키는 시네포엠.

- 한국시네마테크

- 한국시네마테크

by Jean-Luc Godard

장 뤽 고다르와의 대화.Interview with Jean-Luc Godard, 'Goodbye to Language'(2013) 1/2

The legendary director Jean-Luc Godard talks to CPN about his philosophies, his career and his new film 'Adieu au Langage'(Goodbye to Language, 2013), which premièred at the 2014 Cannes Film Festival.

'언어와의 작별' (Goodbye to Language, 2013) - 예고편.Trailer

'A married woman and a single man meet.

They love, they argue, fists fly.

A dog strays between town and country.

The seasons pass.

A second film begins…'

- Adieu au Langage, 2013

film: '언어와의 작별' (Goodbye to Language, 2013) by 장 뤽 고다르.Jean-Luc Godard

고다르는 '언어와의 작별'(2013)에서 3D 이미지를 활용하며 전복적인 방향을 새롭게 제시한다. 스토리를 해체하고 각종 기호와 상징을 은유적으로 펼쳐놓는 이 영화는 당신이 기억하고 학습한 영화언어와의 작별인사이자 새로운 가능성과의 만남이다.

‘진리는 아름다움의 광채’라는 플라톤의 인용구로 시작하는 실험적인 시도는 끝내 모든 언어의 의미마저 해체하며 관습에 종말을 고한다. 어떤 종류의 해석을 요구하는 영화가 아니라 자꾸 무언가에 대해 되묻고 싶어지는 욕망의 충돌.

많은 평자들이 스탠 브래키지의 '독 스타 맨'(1964)과 비교하는 것은 우연이 아니다. 조너선 로젠봄의 표현에 따르면 “특정 언어와의 작별이 아니라 500년에 걸친 이미지 지각의 역사와의 싸움이다”. 해가 갈수록 더 치열하게 고민하는 83세의 고다르.

2017-07-26

Master Class: 라스 폰 트리에 (덴마크, 1956-): "관객을 위해서가 아니라, 나 자신을 위해서 만든다“

Lars Von Trier

관객? 무슨 관객?

어쨌든 내가 중요하게 여기는 것은 하나 있다. 관객을 위해서가 아니라 자신을 위해서 영화를 만들어야 한다. 관객을 생각하기 시작하면, 방향을 잃고 실패를 피할 수 없다. 물론 다른 사람들과 커뮤니케이션을 하고자 하는 욕구가 분명 있을 것이다. 그러나 그것을 영화 전체의 기본으로 삼으면 절대 잘되지 않는다. 만드는 사람 자신이 원하는 것을 만들어야지, 관객이 원한다고 생각하는 것을 만들면 안 된다. 그것은 함정이다. 많은 감독들이 그 함정에 빠지는 것을 보았다. 나는 영화를 보면, 감독이 잘못된 이유로 만든 영화, 감독 자신이 정말로 원해서 만든 것이 아닌 영화를 알아볼 수 있다.

그렇다고 해서 상업 영화를 만들지 말라는 이야기가 아니다. 관객이 좋아하기에 앞서 감독 자신이 그 영화를 좋아해야 한다. 스티븐 스필버그 같은 감독은 아주 상업적인 영화를 만들지만, 그가 만드는 모든 영화는 누구보다 우선 자신이 보고 싶어서 만든 것이라고 나는 확신한다.

대표작

<어둠 속의 댄서> Dancer in the Dark, 2000

<브레이킹 더 웨이브> Breaking the Waves, 1996

<도그빌> Dogville, 2003

*출처: <거장의 노트를 훔치다> (P.155-156, 로랑 티라르 인터뷰 및 지음. 조동섭 옮김)

‘MOVIEMAKERS’ MASTER CLASS: Private Lessons from the World’s Foremost Directors‘ by Laurent Tirard, 2002

Master Class: 기타노 다케시 (일본, 1947-): "무엇보다 우선, 내 자신을 위해 만든다“

Kitano Takeshi

영화는 장난감 상자다

영화는 아주 개인적인 것이다. 나는 영화를 만들 때 무엇보다 우선 내 자신을 위해 만든다. 내가 가지고 놀 멋진 장난감 상자 같다. 물론 아주 비싼 장난감 상자라서, 때로 그렇게 재미있게 노는 게 부끄러울 때도 있다. 어쨌거나 필름이 통에 들어가서, 더 이상 감독의 것이 아닐 때가 오고, 그 뒤로 영화는 관객과 평론가의 장난감이 된다. 그러나 누구보다 앞서 나를 위해 영화를 만든다는 사실을 부정한다면 정직하지 않은 일이다.

대표작

<키즈 리턴> Kids Return, 1996

*출처: <거장의 노트를 훔치다> (P.127, 로랑 티라르 인터뷰 및 지음. 조동섭 옮김)

‘MOVIEMAKERS’ MASTER CLASS: Private Lessons from the World’s Foremost Directors‘ by Laurent Tirard, 2002

Master Class: 왕가위 (중국, 1958-): "자기가 왜 영화를 만들고 있는지 알아야 한다"

Wong Kar-wai

자신의 시를 창조하라

마지막 한 가지. 감독이 되려면 정직해야 한다.

다른 사람에게 정직한 것이 아니라, 자신에게 정직한 것을 말한다.

자기가 왜 영화를 만들고 있는지 알아야 한다.

대표작

<화양연화> 2000

*출처: <거장의 노트를 훔치다> (P.140, 로랑 티라르 인터뷰 및 지음. 조동섭 옮김)

‘MOVIEMAKERS’ MASTER CLASS: Private Lessons from the World’s Foremost Directors‘ by Laurent Tirard, 2002

Master Class: 에밀 쿠스트리차 (유고슬라비아, 1954-): "자신의 영화를 만들어야 한다. 자신을 위해 만들어야 한다"

Emir Kusturica

원칙으로서의 주관성

젊은 감독들이 저지르기 쉬운 최악의 실수는 영화가 객관적인 예술이라고 믿는 것이다. 영화감독이 되는 유일하게 올바른 길은, 자기만의 관점을 갖고 영화의 모든 수준에 그 관점을 씌우는 것이다. 자신의 영화를 만들어야 한다. 자신을 위해 만들어야 한다. 물론 그 영화에 대해 자신이 좋아한 것을 다른 사람도 좋아하기를 희망할 수는 있다. 그러나 관객을 위해 영화를 만들려고 하면, 관객을 놀래킬 수 없다. 관객을 놀래키지 못하면, 관객이 스스로 생각하거나 결론을 끌어내게 만들 수 없다. 그러므로 영화는 무엇보다 먼저 감독 자신의 것이다.

(P.147)

매번 첫 영화인 듯 접근하라

영화감독은 영화를 만들 때, 자신이 촬영하고 있는 것에 자극을 받아야 한다는 단 한 가지 미학적 목표만을 가져야 한다. 내 심장이 빨리 뛰면 그 씬은 잘 됐음을 알 수 있다. 내가 영화를 만드는 이유는 바로 이런 기분을 느끼기 위해서다. 영화를 세상에 내놓는 행동으로 나는 황홀해져야 한다. 내가 그런 감동을 가질 때, 나는 이 감동이 스크린을 뚫고 나가서 관객에게도 전달된다고 믿는다.

이 동감同感을 얻기 위해 매 영화마다 그 영화가 맨 처음 영화인 것처럼 다가가야 한다. 매너리즘에 굴복하지 않아야 하며, 시험과 발전을 멈추지 않아야 한다.

(P.150)

대표작

<집시의 시간> 1989

*출처: <거장의 노트를 훔치다> (P.147 & P.150, 로랑 티라르 인터뷰 및 지음. 조동섭 옮김)

‘MOVIEMAKERS’ MASTER CLASS: Private Lessons from the World’s Foremost Directors‘ by Laurent Tirard, 2002

피드 구독하기:

글 (Atom)